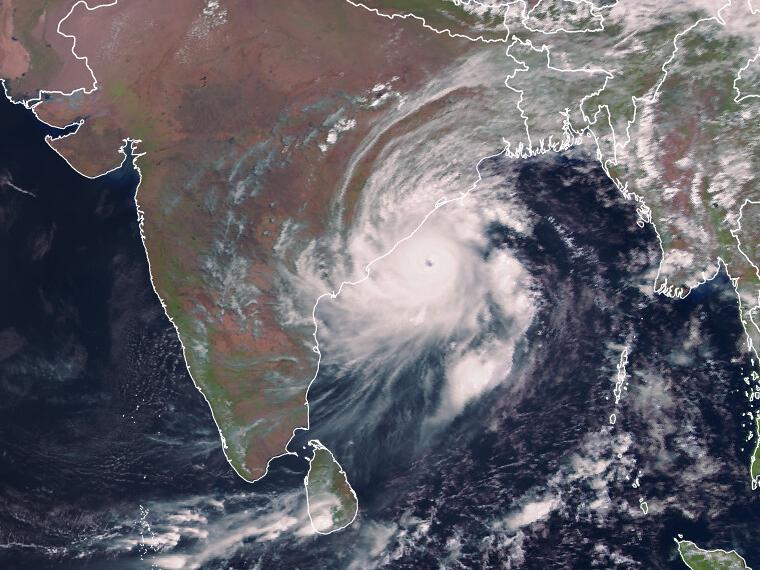

Satellite view of the Cyclone Fani as it hit India on 2 May 2019 (Copyright: 2019 EUMETSAT)

By Patrick Fuller

Extreme weather events now account for 90% of major disaster events globally. The number of weather and climate related disasters has more than doubled over the last twenty years and unless urgent action is taken to address the climate emergency, Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America could be dealing with a combined total of over 140 million internal climate migrants by 2050.

The World Bank estimates that the global economy loses US$520 billion every year as a consequence of disasters which push 26 million people into poverty. But on a positive note, lives lost to disasters are decreasing, thanks largely to improvements in early warning systems which enable countries to reduce risks and be better prepared.

On 29 October 1999, a record-breaking ‘super cyclone’ barrelled into the Indian State of Odisha from the Bay of Bengal. Packing wind speeds of 260 km/h, the cyclone claimed almost 10,000 lives, leaving the government with a US$4.4 billion damages bill. Fast-forward to May 2019 when Cyclone Fani, a powerful category 4 cyclone struck the same area. This time, damages topped US$8 billion but lessons learned from the 1999 super cyclone meant that only 64 lives were lost.

The super cyclone tragedy had prompted the Odisha State government to adopt a “zero casualty” policy for natural disasters. In advance of Fani’s arrival, timely early warnings from the Indian meteorological department coupled with mass evacuations involving more than 45,000 volunteers, meant that a record 1.2m people were moved to safety in less than 48 hours.

Extreme weather events were seen as the most prominent risk in the World Economic Forum’s 2018 Global Risks Report and there is no doubt that investments made in early warning systems coupled with effective actions on the ground, save lives and reduces the humanitarian and economic burden of disasters. Every US$1 invested in risk reduction and prevention can save up to US$15 in post-disaster recovery but, despite advancements in hazard forecasting tools and technology, there remains a critical gap between those who monitor and generate hazard warnings and those in communities who should be on the receiving end. This is the “last mile challenge”.

The devastating 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami was perhaps, a watershed moment where poor monitoring systems and a lack of timely warnings contributed to the deaths of over 200,000 people. They were taken by surprise when a massive 9.1 Magnitude earthquake off the coast of Sumatra in Indonesia, triggered tsunami waves which devastated coastal communities in 13 countries. Since then, international bodies, together with countries and regional entities have collaborated on a range of initiatives to improve forecasting and early warning systems. These include the Climate Risk Early Warning Systems initiative (CREWS) which supports 80 least-developed countries and small island developing states to develop effective, multi-hazard, gender-informed early warning systems.